Tasmania

The most underrated and most introverted place in the world.

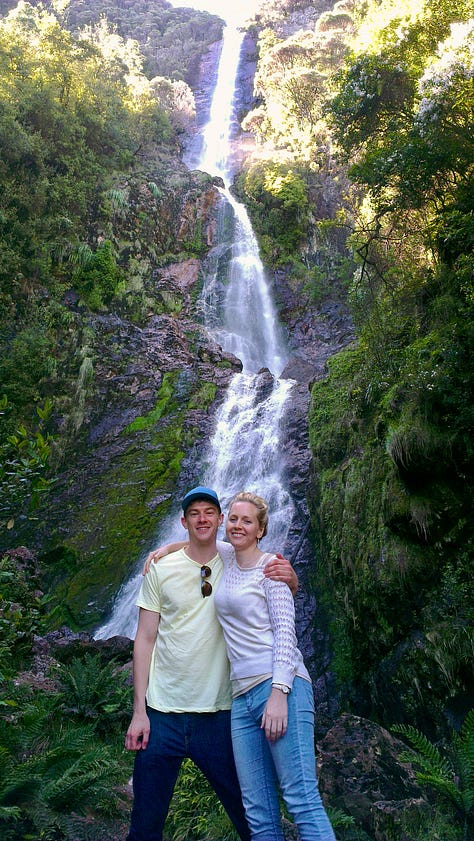

There’s no question that Tasmania is underrated. It has astonishing mountain hikes through wholly unique ecosystems with grand old trees that inspired an environmental movement. It has huge, beautiful beaches with squeaky sand. It has far-flung old mining towns that evoke end of the earth. It has the best food and drink in the world: Cheese with a somehow strong and subtle flavour, bread that I never knew could be both fluffy and dense, crispy-skinned duck that just melts, and the best whisky in the world. It has even contributed to how museums modernised throughout the world, getting critical acclaim for the Museum of Old and New Art. We actually forget that before MONA, museums were stuffy affairs without technological amenities.

But the introversion of the people kills me. Getting information is like pulling teeth. We visited Lark Whisky’s bar, The Still, because my friend said they had a huge range of Tassie whiskies. However, for some reason, there wasn’t the huge range he remembered, and we were curious. We didn’t ask the waiter because his opener for taking orders was, “Talk to me.” I get the casual, efficient vibe he’s going for, but it didn’t help us. We googled and still, no answers. As we were paying our bill, my friend asked, “I came here a while ago and I remember there was a map of Tassie—” but the bartender cut him off, “I’ve only been here 7 months, so I don’t know about a map.” My friend finished his sentence, “It was a map with all the whiskies of Tasmania. Has there been a change in management or…?” The bartender repeated himself, “No. No. I don’t know about a map.” I noticed he was physically self-soothing, lightly rubbing his arm due to the discontent he felt talking for 30 seconds.

Another option would have been, “Oh yeah? I dunno, sorry, you could ask one of the other guys here.” I’m not expecting what I’m used to in New York of American extrovert-level engagement, which would be something like, “Oh wow, really? You sure it was here? When did you come? Let me ask the guys for you. Did you have a good time tonight? You like whisky? Oh, you live locally. Maybe see you again sometime? My name’s John. What’s yours?” I could go on for hours describing the obvious ways to both resolve the question and improve human connection. But at least now I giggle inside when I remember him saying, “I don’t know about a map,” as if under interrogation.

Another example was at a bottle shop, where I at least got information, but not much else. I asked the cashier if he had any mixers, “Last fridge over there,” he said. I returned relieved, “Oh wow, you have so many. That’s great. I didn’t expect you to have any at all! That’s really helpful.” He didn’t respond at all. He just scanned the drinks, never looked at me, and said, “Just tap there.” That was it. He wasn’t busy; I was the only customer. But what’s interesting is that I didn’t think he was unkind at all; he seemed positive and had helped me instantly when asked. He just felt no need to respond, verbally or non-verbally.

I even discovered that introversion is built into their spaces when I tried one of my favourite things: Going to a bar by myself. I visited one of their beautiful bars, “In the Hanging Garden,” which looks how it sounds. I enjoy the feeling of being around people for my extroversion, so a bar is great for an occasional chat or just vibe while I write or think. But it was a serious challenge just to sit down. I thought I must’ve missed something because there was literally nowhere for one person to sit unless I took a huge five-person table for myself. I did do that, but eventually felt bad when I saw a group of women looking for a table. I waved them over and left. Not just were the tables for groups only, but they were also separated from each other by a meter or more, and even an igloo.

I imagined how sad it would be for someone who was transferred here for a 6-month work project and needed some human interaction. I visualised them and genuinely felt sad for this imaginary human, who I’m sure isn’t imaginary.

I share these insignificant examples of introversion instead of many others precisely because they are small. They remove many of the possible variables. We weren’t hitting on people, nor were we trying to get money or sell something, or even wanting these people to like us.

Introversion isn’t bad, of course, but extremes of anything, especially in homogenous groups, can create problems. Tasmanians are clearly clever and creative, yet they are deeply reliant on federal funding, being the largest state recipient of grants by far. There isn’t a shared vision for the future that could alleviate some of this mainland dependence. While introversion is great for generating ideas, extroversion is essential for sharing them.

Tasmania has achieved visionary feats before with its museum and world-class whisky, but they’re exceptions that prove the rule. MONA and its festival, Dark Mofo, were driven by one eccentric multimillionaire. Their most lauded export is a quietly savoured drink that is judged on its objective quality—no discussion needed.

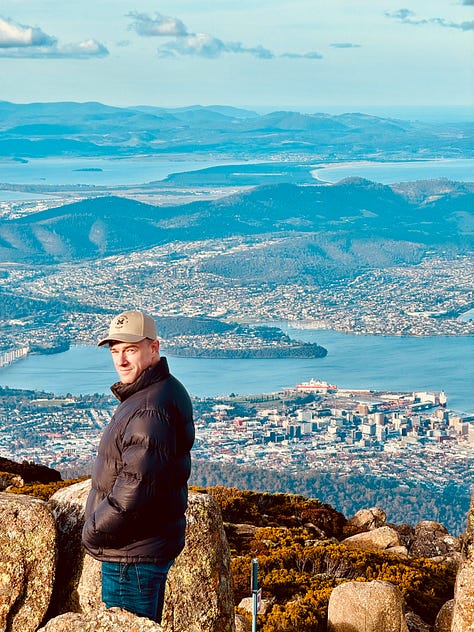

I recall the first time I saw Hobart as a backdrop while one of their many politicians was speaking. There was nothing distinctive. No arts institution, no feat of engineering, no concentration of skyscrapers. It’s like the whole city is saying: We don’t know what our vision is either. Depressingly, all that’s distinctive is a casino. And a drab 70s one at that.

The island is clinging to past visions, with industries not economically viable and actually harming viable alternatives, such as tourism. An 84-year-old pulp mill, an 108-year-old zinc smelter, and a 200-year-old logging industry rely heavily on government support, with each worker costing between $20,000 and $300,000 in government grants. You could cut out the middlemen and simply put everyone on welfare, and it would cost less. And at least then you’d save an ecosystem or two.

Seeing my first platypus in the wild in the town of Geeveston

There is one vision for the future that’s the talk of the town: A new waterfront stadium. But it’s more of the same, almost like Tasmanians are used to the idea that businesses are meant to cost money rather than generate money. According to all reports, it’s not economically viable, and, amazingly, the people agree. A wide margin does not support it, but the politicians on both sides simply lack alternative ideas. And who can blame them: The stadium benefits from the social substructure of sport to communicate and campaign for it.

There are interesting ideas for the waterfront that have a decent chance of making money, but this is the tragedy of Tasmania: Good ideas float off into the mist of the Huon.

I imagine a well-thought-out alternative design being humbly advocated for by a nerdy, unfashionable glasses-wearing urban planner. He emails his plan to a committee—never presenting it, of course—and ends with, “No, I don’t know about a map.”

You just have to visit Tasmania to learn about it because you’ll never hear how great it is. Certainly not from Tasmanians.

Love your work Clinton! Tasmania is my idea of paradise in many ways, but I do miss the easy extroverted chit chat with strangers that I experienced in North America, and I long for more visionary feats of engineering and urban planning.

Interesting reflections, Clinton.

Brand Tasmania identified the persona of the Tasmanian as “an ambitious introvert that loves nature.” That’s not me (I like nature but certainly not an introvert) but it is many.

Your point about not hearing about Tasmania from Tasmanians can be challenged though. Some research found that Tasmanians are more likely to recommend their home state of Tassie as a place to visit compared to every state ie people from Victoria aren’t as likely to recommend Victoria as a place to visit.

It’s wild but often it may be the case that the people do their thing and hope others notice. That’s kinda why I do TEDxHobart: I find people doing things quietly behind the scenes and give them a spotlight to share it.