Ketamine Therapy

My experience unlocking parts of myself that conventional therapy couldn’t reach.

There are so few moments in your life when you think: ‘That there. That’s when I was fundamentally changed.’ That’s how I would describe my ketamine therapy a month ago. I saw things that I didn’t know existed. Not hallucinations, but things I have been avoiding, with breadcrumbs showing their existence coming into view all at once.

That’s actually what the process feels like, too, during the intravenous infusion: Everything happening all at once. I remember having numerous interconnected thoughts and trying to follow them to interesting conclusions; initially, I would will myself to reach that fascinating insight. But I was hit with a sense of: ‘It’s OK. You always have this in you.’ Stimulated and alleviated all at once.

The first session is the slowest and lowest dose, 30 milligrams over 90 minutes, to monitor your response, as your body is unadapted. Testament to that lack of adaptation, it was my most intense. This is despite the latter four sessions being incrementally higher doses over shorter periods, reaching 45 milligrams over 65 minutes by the fifth, along with a nausea aid which I hadn’t previously felt I needed. I did 5 sessions instead of the recommended 6 because at $525 each, I thought I could shave off one, since doctors always give an extra dose to be sure. I was here to discover trauma, not for a fun time.

I was brought into a nice, if clinical, small room with aluminum Venetian blinds, letting in reflected light from the office buildings of the Financial District. An intake nurse asked about my state of mind, recapped that the experience could feel floaty, that I may have hallucinations, but they’re not common, and a few other details. The previous one-hour intake with the supervising doctor, Dr. Glen Brooks, was very thorough already, and I had been reading about ketamine for years. I especially liked that he said I didn’t need to do or expect anything during the infusion, as the drug will do all the work, both at the time and in the days and weeks ahead. That tracked, given this treatment was discovered by accident. Administered to soldiers in the Vietnam War for pain, it surprisingly treated the newly discovered PTSD. I can’t imagine doctors in a field hospital waving incense, lighting candles, or playing Native American folk music, so I was relieved that I didn’t have to either.

I began getting comfortable, lying back in my chair, pulling the blanket into position, and turning away as the nurse connected my vein. In her Slavic accent, she said to press the call button if I needed anything, almost like I would be disappointing her if I didn’t. She dimmed the lights and said she would be back every 20 minutes to check on me.

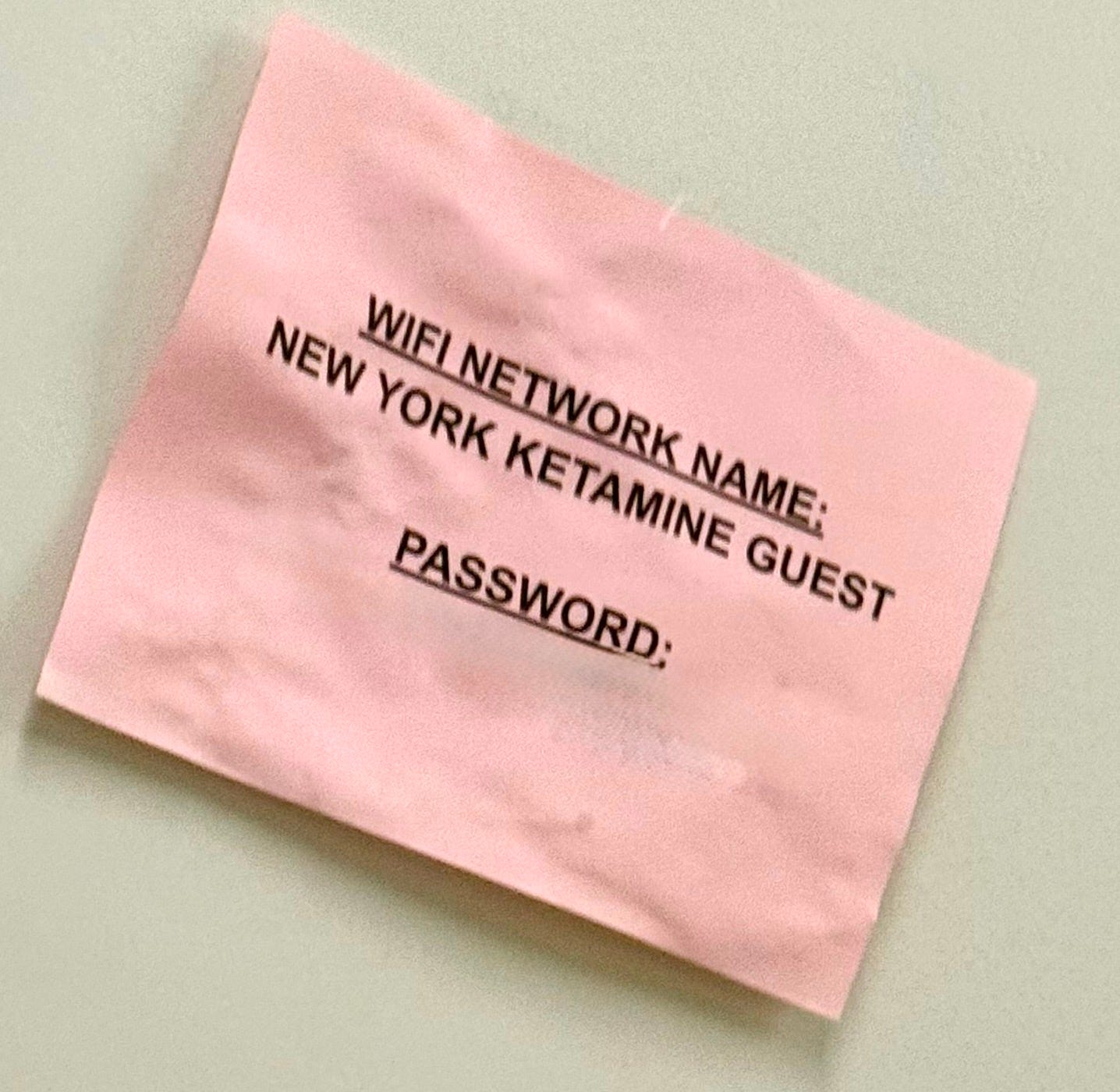

Left alone, I looked around the room, finding humor in the quotidian piece of paper stuck on the wall with the wifi password. It reminded me that it was okay to use my phone, although Dr. Brooks advised no politics, and I couldn’t agree more, as someone who really feels politics. There wasn’t much else, except for a cup of water and a seemingly purposeless box of tissues. The kind of box left in a room to create a sense of amenity.

I lay with songs on repeat, which may be a neurodivergent need rather than a part of the experience. One of the songs was Dice by Finley Quaye with Beth Orton, and that’s when I started to lose it. I remember thinking how deep the song was because it’s called “to say” in Spanish, completely forgetting the English meaning of the word.

However, I knew the deeper resonance was Orton’s voice, and its evocation of her songs, one I’ve listened to in my happiest morning-after moments, “Central Reservation,” but also its diametric opposite, “Stolen Car.” It’s about wanting to belong, feeling at sea, standing for something while misunderstood, and ultimately, unloved.

It welled up in me, and for someone with a constant inner dialogue, I don’t remember articulating it. The crying just emerged, and I said in my head, “I’m sorry,” and I cried more. I cried like I had never cried before. I checked my chair for a puddle of water, but it was bone dry; it just felt like an ocean of sadness. I kept saying on repeat, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry.” But I knew it wasn’t enough; I could never apologize enough. And so I kept crying for 40 minutes—I guessed that’s how long because the nurse entered at two intervals, saying nothing, checking my infusion bag, and leaving. It wasn’t a howling but a sobbing, and eventually, I thought I couldn’t breathe. Then I saw the tissues and blew my nose. I could breathe; I just needed the purposeful tissues.

I don’t know at what point I started visualizing the entity I was apologizing to, but he was a sweet, kind thing, with a balloon-like face, and looked like Junior from Duolingo—a recent, daily reference. He was tiny, sitting in a dark, cold pit, not saying anything, not capable of saying anything, and knowing nothing needed to be said. I would dry my tears and think it was done, and then apologize again and cry more. I can still cry if I think about it.

A doctor friend, albeit in economics, but an avid researcher nonetheless, later explained what was happening, and it perfectly aligns with what the research indicates ketamine treats. The walls in my Internal Family System—this group of identities people create from trauma—had broken down, and the dominant Protector was confronted with the Inner Child, whom he keeps in line. He had been chastised for making mistakes, isolated, and blamed for everything the Protector, whom I called The Monster, felt had gone wrong. I could never be powerful enough, let alone want to, inflict this level of pain on any actual person. It was also the singular time I knew, without a doubt, that an apology would not be enough.

Physically exhausted, I stopped apologizing and started pulling myself together, and just rested. The nurse returned, and the whole saga felt like it had lasted only 20 minutes instead of almost 2 hours. She said I could stay as long as I liked and was reassuringly present, yet space-giving; she’s seen enough people go through this. She later told me not everyone cries in the first session, but some do. She said it in a way that intuited that I needed this.

It felt weird leaving by myself and entering the bright, wide world, as if I should have had someone take me. This was another realization that I don’t ask for help, despite knowing the research on how much people like to help. I didn’t think I could walk, but I tried, and to my surprise, I felt completely fine, walking straight with no wobbles. I kept walking and got to the 9/11 memorial, drawn to the open and contemplative space, but my mind also felt more manageable juxtaposed with a literally monumental tragedy. And I did turn to my friends for help.

Finding myself in FiDi

I started explaining the experience and had to articulate to myself for the first time where it came from. People have told me enough times that I am too hard on myself, so it has been somewhere on my mind. It’s also odd that I had always been curious about these treatments for trauma, and had considered MDMA too, as the other, albeit lesser researched, but still strong option. In my intake, after describing my childhood, which involved undiagnosed neurodivergence, the sudden death of my brother, and being gay, Dr. Brooks said I was a perfect candidate. I believed his honesty deeply while not knowing what I was in for.

The very next session felt positively placid, how could it not? Just a floaty, restful experience in a chair in a room. But it was outside the room that I noticed the change. I felt explosively creative, and it led to this very project you’re reading now. My Inner Child’s unvarnished expression was beginning to surface. I would be walking down the street, talking to him, sending kind but sorrowful thoughts, and extending that kindness to others. I came to identify everyone around me as people with a sweet child inside that I could also connect with and nurture.

In the third session, I realized why they tell you not to make any big decisions on ketamine. Because you feel an immense sense of clarity and decisiveness, which will be right, but you may not have put the practical steps in place to carry it out. I decided to cheat the system a little by making a big decision right before my first session, pressured by the knowledge I wouldn’t be able to after. I booked a flight to Australia for 6 months, intending to live there. And the therapy added a sense of obviousness: Why am I working in this American mine when I have access to the most livable places in the world.

In the fourth session, a breakthrough happened that caught me by surprise. I said to myself, “It’s OK, you were trying to protect us, and you didn’t know any better.” I identified as the Inner Child, and just writing it now makes me cry. I now saw this Inner Child as not an isolated mute in a cave, but a bright, smiling superhero in a red Lycra suit, like The Incredibles. What I didn’t think was possible happened, and every day I forgive the Protector and nurture the Child.

The Inner Child’s thoughts come through unfiltered all the time. For instance, I did something I would normally be incensed to do as a millennial: I entered a bank branch. I needed to cancel a scheduled transfer and was perplexed as to why I couldn’t do it online. I smiled and said, “I really need help with this, and I don’t know what I’m doing wrong.” My vulnerability opened her kindness, and I could feel her eagerness to help. As she requested details, calmed by her kindness, I started looking through the app. I found the transfer not in the Transfers section, but in the Wires section, and successfully canceled it before she could retrieve my account. I explained, “Oh, this definitely tracks with the sort of mistake I would make.” She laughed, and I left. Kindness towards my own mistakes has brought out kindness towards everyone else’s.

I should add that it’s a Brené Brown-type of kind, which is that it’s about being clear in what you can and can’t do. I have cut short social interactions upon realizing that I can’t bring the warmth I would like to bring because I am unable to experience theirs. A long-suffering people-pleaser always ends up with sharper edges.

By my fifth session, I felt like I was simply going through the motions. I understood why people could get hooked on this because it’s both restful and uplifting—stimulating and alleviating. But for $525 a session, I can get that in more interesting ways. Still, I reminded myself that the value isn’t in the experience itself but in the rewiring it sets in motion.

My interpretation of the research and experience of ketamine is that it throws all the neural pathways up in the air and lets them land back in the here and now, which is why it works for trauma. It says to your brain: ‘Look around, what do you see? Are people trying to hurt you? Are you getting in trouble for mistakes? Has someone died in the last week? No? Well then, why are you defensive?’ It’s not magical, it’s practical.

I’ve heard, and we’ve all heard, of ketamine addiction. There were so many times I thought: ‘It’s so lame that I’m doing what Elon Musk does.’ Having long associated ketamine as the breakthrough trauma treatment, I was now thinking of someone who believes we’re in a simulation and that he is Player One. I had to process this contradiction. First of all, a good thing associated with a bad person has happened before. We separate hot yoga from the sexually abusive artist behind it. I also remember some advice I gave to a startup founder. She was discussing her leadership team structure and was concerned about coming across as not collaborative enough. I told her, “You never have to worry about that.” People this hard-wired for collaboration have already done the work. It’s the people who never ask the question who need the answer. Musk didn’t need more kindness to himself or clarity and confidence in his decision-making. But you do.

Life is what you’re capable of making it, and there’s no insight or experience that can take the wheel. In this vein, I know I need to do the work. I keep thinking about how helpful it was to bring my friends into this with me. Not just their feedback on my experience, but having to clarify to them and for me what it meant.

The sessions had me bringing forward so much kindness for myself and everyone else, but I felt pangs of it slipping. Every session, I would take my Apple Watch off for the needle, but in my last session, I wanted to see my Heart Rate Variability—a good track of emotional health—and put it on my other wrist. In a reflection of the resetting that happens, I was certain my watch was on the side I always wear it. I realized my mistake after the session, but I thought if I can believe that to be true, I can be the kinder person I’ve always wanted to be. I now wear my watch on my right arm as a daily reminder. And as the sunnier Beth Orton song goes, “Today is whatever I want it to mean.”